History of Parker County

By Susan Karnes

Hollywood has long attempted to capture the romantic tale of the American West, an epic drama of cowboys and Indians, the advent of the railroad, and the struggle to carve farms and ranches in an often unforgiving wilderness.

That story is, in fact, the history of Parker County.

For centuries, the Kiowa and Nüma-nu (Comanche) inhabited this land. Nomadic hunters and gatherers, masters of the plains and the horse, the Native American bands lived in seasonal encampments of teepees and followed herds of buffalo.

In the mid-19th century, settlers arrived from nearby Southern states. By 1855, small farms and tiny settlements began to dot the land along the Clear Fork of the Trinity River and Mary’s Creek. A county was formed, with Weatherford its county seat.

The native people of the area sensed a threat—and an opportunity. On one hand, the farms encroached upon the land that the Native Americans roamed. On the other, fine horses and livestock offered tantalizing bounty for the enterprising Comanche and Kiowa.

A few settlers in the new settlements of Center, Alma, Dicey, Newburg, and Elm Springs owned slaves; most did not. The majority, however, were sympathetic to the Confederate cause. As the Civil War erupted, the county voted to secede. By late 1861 most able-bodied men had joined the cause, leaving women, children and the older and infirm to defend homes and property.

With the Civil War came heightened conflict. Raids by the Native Americans were common. Settlers dreaded full moons, since raiding parties often would take advantage of moonlight to steal horses and other valuables. From 1858 until 1872, when peace finally prevailed, Parker County endured more raids, many marked by violence and death, than any other county in Texas.

Tenacious settlers persevered. By 1870 there were schools and churches. Freight wagons ambled to market, piled high with buffalo hides.

In 1875 Comanche Chief Quanah Parker acknowledged profound changes: The buffalo had been decimated, the prairie belonged to settlers, and the future depended on peaceful assimilation. He struck an accord with the U.S. government and led his people into the difficult transition from their nomadic ways to farming on government-issued land in Oklahoma.

After an arduous Civil War and postwar period, by 1878 the Fort Worth-Yuma cattle trail and stagecoach line crossed Parker County, and in 1879 a Texas and Pacific Railway line connected Fort Worth to Weatherford via stations in eastern Parker County. Settlements started to flourish.

In eastern Parker County, one of the oldest settlements, Elm, or Allum Springs, evolved to Willow Springs. To its southeast, a small settlement called Medearis or Medera, after the adjacent Medearis land grant, grew near a railroad stop. A few miles south of Elm Springs a tiny settlement named Anneta, the precursor to modern Annetta, sprouted.

In 1882, Medera became Aledo, a bow to a railroad executive’s Illinois hometown.

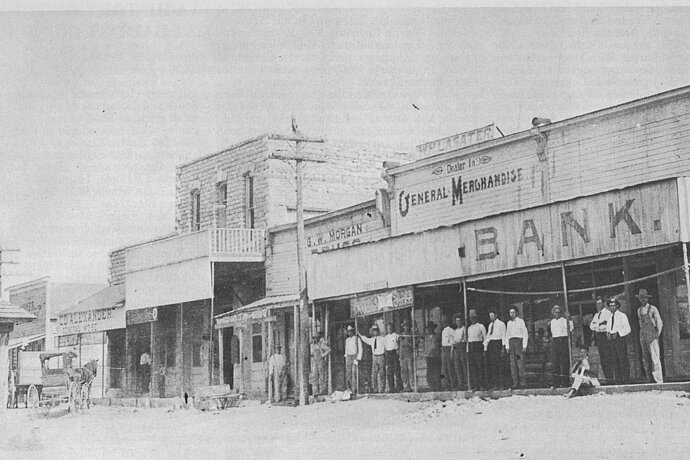

The new town was platted. Businesses faced the tracks on either North Front Street or South Front Street.

Along the former, Bowlen’s offered rooms, haircuts, and buggies for hire. The proprietor of Overmier’s General Store sold dippers of his well water to train passengers. Newt Markum built a drugstore, and on the first floor of his building, J.J. Sears sold axle grease, bacon, and coffins; upstairs served as a Masonic Hall. Sears owned the bank on the east end of North Front Street, a lumberyard, and farms around town. When occasion demanded, he served as undertaker.

As the nineteenth century dawned, the first telephone switchboard arrived; only party lines were available. Aledo citizens built their first school building, a two-room plank structure with a shed on the west side. By 1910, 73 automobiles were registered in Parker County. Prosperous rancher Charles McFarland delighted many a child by offering a lift to the schoolhouse in his two-cylinder Buick.

By 1925 residents drove Bankhead Highway, the first all-weather transcontinental road in the nation. Farming remained the primary occupation on the prairie land filled with wooded valleys. Near Aledo, common crops were cotton, corn, grains, and hay. On the land surrounding Willow Springs, farmers raised cotton, corn, peanuts, and dairy cows.

When the Great Depression hit hard in the 1930s, merchants and farmers struggled. There were bright spots: Mrs. Hamaker, the Aledo postmistress, handled mail while her husband, who had fought in the Battle of Gettysburg, met the train and carried the mail from the depot. Ray Smyth built a mill that employed up to 100; for years it remained the only employer in the area, a fact for which men would thank Smyth for the remainder of his life. Fort Worth businessman W.K. Stripling and partners built a lodge, El Chico, which is purported to have hosted Jack Dempsey, Gene Autry, and Roy Rogers.

Around 1940, Highway 80 was completed; a scenic roadside park and pond proved popular. The Aledo Civic Club hosted Gene Autry at a benefit box supper that raised more than $1,200, a princely sum for the time. And as World War II roared, Lieutenant General William Hood Simpson, a descendent of early settler and Texas state legislator Judge A.J. Hood, rose to prominence as he led the Ninth Army in Europe.

The area’s ranching roots remained strong. In 1946 a group of Parker County men founded the National Cutting Horse Association, an organization that today boasts a membership of almost 20,000. For decades, pens and feeding lots on the north side of the Aledo railroad tracks held up to10,000 head of cattle for market.

By 1980, the area’s proximity to the Fort Worth-Dallas Metroplex and major employers began to attract an influx of residents drawn to excellent schools and a relaxed lifestyle. The Aledo and Willow Park (once Willow Springs) communities incorporated in 1963. In the late 1970s, the cities of Annetta, Annetta North, Annetta South and Hudson Oaks were formed.

Today, the tiny settlements of Alma, Newburg and Prairie Hill are lost to living memory; only fragments of the original Bankhead Highway remain. The area’s rich history is preserved for enthusiasts through Aledo’s original Front Street buildings, the Willow Springs Cemetery and other historic sites, which are enduring reminders of how the West was tamed.